This is the second post in pianist and professor Julian Jacobson’s mini-series for this blog focusing on Beethoven’s most complex master piece for the piano, the ‘Hammerklavier’ Sonata in B flat major Op. 106, which he will be performing in London on Sunday January 11th 2026 at Mill Hill Library. Today, he discusses his past performances and the thorny topic of memorisation.

Find out more and purchase your tickets by clicking here.

No one undertakes the Hammerklavier lightly. It was pretty much a closed book to me until I decided to do my first complete Beethoven sonata cycle: this was in 1988 or 89, I was at a festival in Catalunya coaching chamber music, feeling in a bit of a rut, and suddenly announced to a friend that I was going to do it.

At that point I had only played about ten of them. My younger self had a horror of playing anything “popular”, so I am perhaps the only Beethoven pianist, if I may call myself that, who learnt the Pathétique and Moonlight at the age of 45. My journey towards learning the remaining sonatas began immediately on my return to London with op 90, of which I barely knew more than the opening bars.

Early on I decided that I could not even begin to plan a first cycle till I had got the Hammerklavier at least basically under my belt. I slogged away at it and finally felt ready to put it into a recital at Dartington around 1992. I still had many sonatas to learn, and in 1994 – with the security of a salary as Head of Piano at the Royal Welsh College of Music and Drama – I took the whole summer off and learnt the remaining dozen or so sonatas, mainly the early ones but also including some prickly specimens like the F major op 54. Between 1994 and 96 I did my first three cycles, at Christ’s Hospital, St John’s College Oxford and the Welsh College. I did another four cycles before I conceived the mad idea of doing them all in one day: this was in 2003 in St James Piccadilly in London, and I’ve since done it another four times, each time swearing that I’ll never do it again.

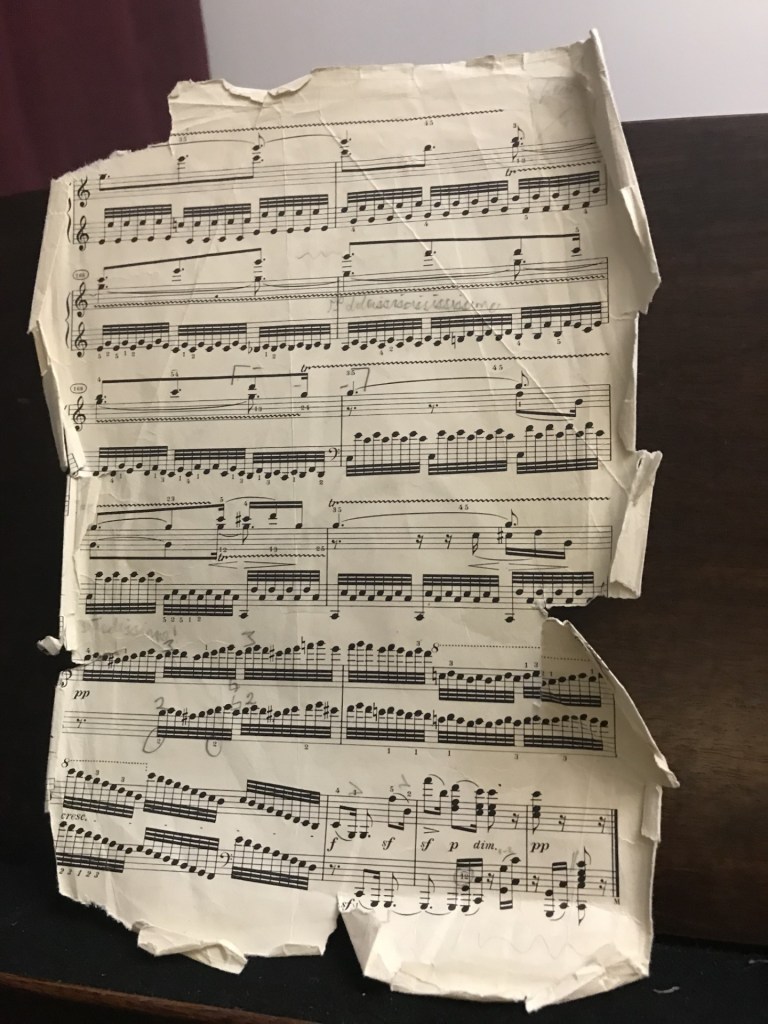

As for the Hammerklavier, in my early cycles I did it from memory, like all the others. But it’s so cruelly taxing for the memory, as in every other way, that in my “marathons” I have generally put the score up for it. The first two movements are ok, but some of the detail in the 16-minute Adagio is torture to nail down, and as for the bristling fugal finale….well, I was delighted to read somewhere that Busoni, no less, never played the movement from memory but put the score up just for the finale. I’ve done that once or twice myself. As always there are gains and losses: you won’t get lost if you have the score there, but for large stretches it’s almost easier to play from memory as your hands are leaping around so much. And there’s a special magical intimacy in the Adagio when done from memory, one seems to be sharing Beethoven’s profoundest emotions directly and unfiltered with the audience.

The question always arises as to how much one should listen to other pianists. At the beginning I listened extensively to all the greats (and many of the not-so-greats), evaluating, comparing tempos, articulation, pedalling and also minute variations of the actual text that are so much an issue in the sonatas – none more so than in the Hammerklavier! This would sometimes confuse my own reactions and make it harder to pin down a performance that felt genuinely my own. So for my last two “marathons’ in November 2022 I took the conscious decision not to listen to any Beethoven piano sonatas at all (except of course when teaching, judging etc.). If one happened to start on the radio when I was out of the room I rushed to switch it off! That way I felt that I “owned” my interpretations, right or wrong. This was particularly important in the Hammerklavier when so many great pianists have taken such divergent views, particularly in relation to the tempos of the outer movements with Beethoven’s hyperactive metronome marks, ranging from the marked 138 to the minim (Schnabel, famously or infamously) to Sokolov’s 80. Next post will go into this and many of the other interpretative conundra that face us.

Image credit: Roger Harris

Top Image: A painting from 1840 by Josef Danhauser, “Liszt at the piano” with Byron, Rossini, Berlioz, Georges Sand and others, possibly depicting Liszt playing the ‘Hammerklavier’.